showCASE No. 99 I Climate Calling: Inside EU Cities’ and Regions’ Green Race

As the United Nations (UN) Conference of Parties (COP25) approaches together with the widely announced European Green Deal of the incoming European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the end of year is once again dominated by climate-related discussions. What is different from previous pre-COP-bubble-talks, is far greater appearance of non-state actors committed to move climate actions forward.

There is business and there are specialised NGOs. Cities, which will soon be inhabited by two thirds of the world’s population, are already on the front line of climate change, and climate hazards already have some costly impacts on services they provide. At the same time, urban areas are key contributors to climate change being responsible for around 75% of global CO2 emissions. In other words, cities are both “a cause of and solution to climate change”. UN Secretary-General António Guterres believes that “cities are where the climate battle will largely be won or lost”, calling mayors “the world’s first responders to the climate emergency”. With this plea in mind, negotiators will soon gather in Madrid for COP25 (December 2 to December 13, 2019) to carry off rules for carbon markets and discuss post-2020 changes in detail.

Bearing in mind that cities account for the majority of global CO2 emissions – with transportation and buildings among the largest contributors – tangible progress can be achieved only with coordinated actions at the global, national and local levels. Urban voices cannot be ignored as cities from all over the world are already showcasing the best climate resilience strategies and ideas. While some invest in renewable energy sources (RES) or energy efficiency schemes, the others focus on regulations limiting emissions from the industry.

But are cities actually in position to negotiate the climate future? Are their advocacy endeavours at all recognised?

Official framework

Although the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) entered into force on 21 March 1994, it was only around COP21 in 2015 when a notion of “climate action” at all possible levels started gaining in importance.

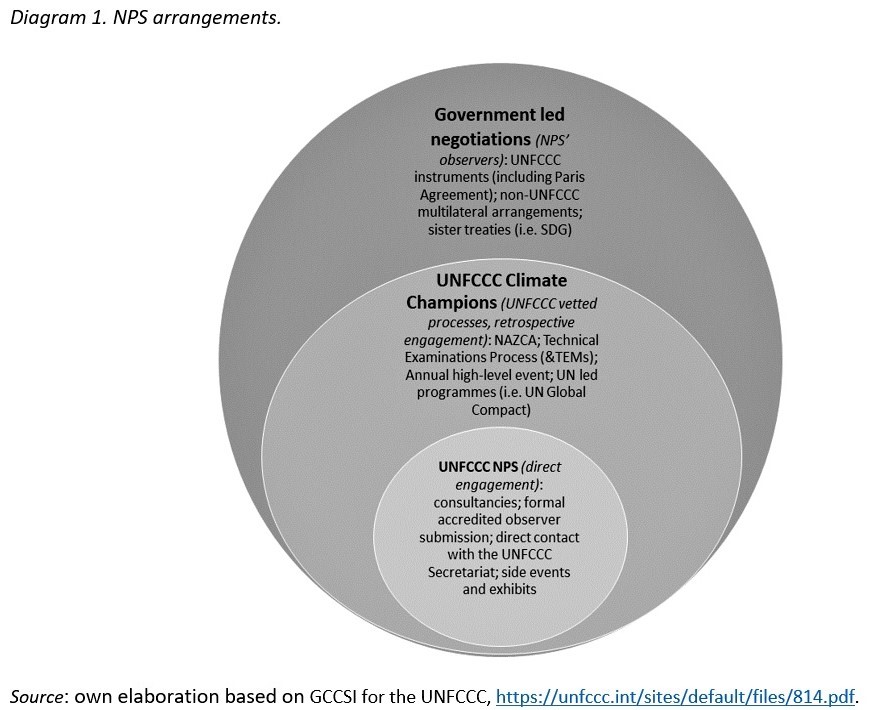

Ever since, the Non-Party Stakeholders (NPS), including cities, regions, and investors, among others, do their best to mitigate or adapt to climate change. The Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action has been set precisely in order to strengthen collaboration between key stakeholders and prove that climate resilience can only be achieved at the multilateral level. The framework allows those interested – particularly subnational actors – to consult their ideas via multiple channels and initiatives. This can be done, among others, via:

- the Data Partnerships for the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) web portal which supports reporting and tracking activities as it presents the Global Climate Action endeavours through an interactive map-based interface;

- the Yearbook of Climate Action – an annual publication documenting the most tangible approaches to deliver Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs);

- two UNFCCC Climate Champions responsible for the overall management of the NPS engagement, organisation of Technical Expert Meetings (TEMs) as well as the scaling-up and introduction of new initiatives, and coalitions;

- Climate Action events and exhibitions at COPs;

- or during the Regional Climate Weeks.

The UNFCCC also invites cities and regions to thematic workshops or working groups working throughout the year. The statistics on non-Party stakeholders engagement confirm that these actors’ involvement in consultations is growing rapidly and European NPS are the most active ones.

What is more, the UNFCCC is in position to ask NPS to submit their oral or written positions on selected negotiation items individually or collectively (i.e. as a group of cities from one single region). Typically, twice a year and just before each COP, the UNFCCC convenes negotiation sessions or ad-hoc specific negotiation sessions on one negotiation item only. The Local Governments for Sustainability network (ICLEI), serving as the Local Governments and Municipal Authorities (LGMA) focal point, is responsible for preparation of interventions on single negotiation items or for the High Level Segments.

Despite these numerous accomplishments, the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action is up for renewal. While some technical discussions are already taking place to agree on the “space” for cities and regions in the UNFCCC framework in post-2020 reality, broader consultations will be needed to develop a detailed agreement before current arrangements expire next year. There is no doubt that this will need to be done during COP25 as without a clear mandate and push for a less centralised, more flexible and open system, there is a substantial risk of delay after current scheme expires at next year’s summit in Glasgow. Thankfully, unlike in advance of the Parisian COP, there is no clear national opposition towards engaging non-Party stakeholders into a more institutionalised climate agenda. While some underline the primacy of Parties in the negotiation scheme, climate action by local entities is considered supplementary in efforts towards sustainability. For the upcoming COP presidency, lying a strong foundation for climate action and subnational parties’ engagement in post-2020 reality could become the biggest success.

Local groups and alliances

The official UNFCCC framework, apart from the already mentioned ICLEI – a climate leadership global network involving more than 9000 cities and regional authorities – is supported by multiple organisations and urban networks in which EU cities, and regions are particularly active. As many as 9465 cities and 278 regions are already registered on the NAZCA climate commitments platform, and those representing the EU are dominating the counter. It is no different in other climate-oriented urban networks:

- The Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy, which represents more than 10 000 cities from six continents, is a network of 7908 EU cities. The organisation offers its support via 3 separate initiatives: 1) Innovate4Cities scaling urban research and innovation (R&I), 2) Data4Cities – an initiative on data usage for city-intelligence, and 3) Invest4Cities focused on large-scale financing urban projects;

- The Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance – a network of global cities willing to cut their CO2 emissions by at least 80% by 2050 or sooner. Out of 21 cities currently allied, 6 are based in the EU (+ Oslo);

- C40 – a network of 94 cities, out of which 16 are located in the EU, actively engaged in achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement and broader sustainable development. The organisation runs numerous initiatives on specific climate-oriented subtopics and supports its member cities in networked urban climate change actions and scaling of urban experiments.

Showcasing action

Going green has become something to boast about, and organisations like C40 benefit from it. Their “Reinventing Cities” worldwide competition launched in December 2017 for local innovators to transform local spaces with energy efficient and resilient buildings and other infrastructural sites, has gained a lot of public attention. Most of all, it helped the winning teams from Chicago, Madrid, Milan, Oslo, Paris and Reykjavík in proving that serious emission reductions can align with beautifully designed infrastructural sites – new beacons of urban sustainability. Out of 15 winning projects announced earlier this year, 10 are based in the EU (France – 2, Italy – 4, Spain – 4), 4 in the EU’s closest climate-allies (2 in Iceland, 2 in Norway), and only 1 in the US. European architects, designers and innovators were recognised for their ability to transform run-down neighbourhoods into “innovative urban spaces that actively contribute to community health and well-being”. The 15 projects will be executed with the support of C40 and municipal authorities and private sector in order to demonstrate how partnerships can enable shaping of the resilient urban future. As the competition is held under “open source” policy, each winning project will serve as a model for environment-friendly developments across the world. The competition is ongoing and more winning projects will be announced soon.

Other cities, i.e. Copenhagen or Stockholm, instead of focusing on external competitions, work hard internally to achieve net-zero emissions and become fossil-free by 2025 and 2040, respectively. Interestingly, the Danish capital is planning to achieve this ambitious goal while continuing to grow in traditional economic terms. Despite popular opinions that transition to green economy equals downturn, the city’s decarbonisation is happening alongside a 24% urban growth over two decades. Copenhagen has already reduced its CO2 emissions by 42% compared to 2005, and while challenges related to energy inefficient infrastructure and transportation remain, the city is on track to achieve its ultimate goal.

A just transition

In her initial strategy introducing the European Green Deal Ursula von der Leyen rightly suggested that not all cities and regions start energy transformation from the same point. Although the incoming European Commission President strongly believes that all EU regions share the same ambition of becoming climate neutral by 2050, some may need more tailored support than others to achieve this ambitious target.

Out of 41 mining regions in 12 EU countries, 10 are in the Visegrad countries, and as many as 6 of them are located in Poland. It was one of the reasons why the Polish Presidency of COP24 came out with the initiative to sign the “Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration” calling for fair treatment of communities affected by the urgent need of energy transformation. According to Brian Kohler, Director of Sustainable Development at IndustriALL – a trade union representing 50 million employees in 140 countries – the declaration signed in Katowice in 2018 gives impetus to the official inclusion of justice in global climate negotiations. The document’s main postulate is to create “high-quality jobs” in the alternative fuels sector, and to intensify dialogue with those who could possibly suffer the most from the green transition. This can only be done by informing them about opportunities stemming from the switch to green economy.

It remains unknown to what extent the incoming EC President standpoint has been impacted by the Declaration, but in her first political guidelines, von der Leyen indeed promises to support the most affected EU regions through a new Just Transition Fund as “this is the European way: we are ambitious and we leave nobody behind”. To support the transition holistically, a more educational component on necessary behavioural changes has been promised within a framework of the European Green Deal. The European Climate Pact is supposed to bring all the local and regional actors together so that they understand how important each small pledge is.

Catalysing action

Just before the UN Climate Action Summit held in September 2019, representatives of networks of cities, regional governments, investors, NGOs, and businesses from all over the world sent a letter to Carolina Schmidt, COP25 President, underlining that it was high “time for action”. With the Marrakech Partnership terminating at the end of 2020, the question arises on role that urban and regional climate action should play in the UNFCCC process. The growing role of NPS since COP21 is an evidence of regular developments in global climate-related governance – multilevel governance which can be inclusive and flexible. The UNFCCC climate action space needs to build on that and ensure that the local and regional voices will be heard.

One thing remains certain: even in case of the biggest COP25 negotiation failure, EU cities and regions will not need any formal frameworks to move the green transition forward. Whether it is about becoming the first climate-neutral city worldwide, or networking with other local entities to discuss common challenges so that the response (both mitigation and adaptation) is stronger, the EU urban representatives are well-prepared to answer the climate call. If the European Green Deal is at least partially as ambitious as its initial proposals with all the regulatory, financial and educational incentives in place, there is no doubt that even the lagging (post)carbon-regions will soon join the green race.

By: Karolina Zubel, CASE Economist

Photo: The City of Edinburgh Council building, Flickr, GB_1984, CC BY 2.0