showCASE No. 91 I Eastern Partnership: Reflections After a Decade

The European Union’s (EU) initiative Eastern Partnership (EaP) was inaugurated in May 2009 in Prague as a unifying platform of cooperation with six post-Soviet countries of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine in the areas of economic cooperation, democracy promotion, civil society and social development, trade, energy, security, and environmental protection. A part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) that uses both bilateral and multilateral approaches, the EaP involves the Euronest Parliamentary Assembly forum, Civil Society Forum (EaP CSF), and Conference of Local and Regional Authorities (CORLEAP). They promote further economic integration and political association by providing partner governments with technical and financial assistance and by creating discussion forums. The EaP shows EU’s willingness to reinforce ties with the region, offering various incentives to governments and the civil society to push ahead with democratic and economic reforms. Devised as an alternative to full EU membership and even dubbed ‘light enlargement,’ the EaP focuses mainly on the EU’s bilateral relations based on action plans tailored to individual countries and on a common set of tools, such as the ENP's main financial instrument, the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI), visa facilitation, and sectoral cooperation. Additionally, EuroNest, the EaP’s parliamentary dimension, encourages regional integration by way of a multilateral track.

In the decade since the EaP’s establishment, many areas of cooperation have been explored, and substantial progress has been made under the 20 Deliverables for 2020 initiative, with the Partnership emerging as a unique model of cooperation when it comes to civil society mobilisation. Since the EaP launch in 2009, the EU provided EUR 1.5 billion in support to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the EaP countries and extended over 100,000 loans to enterprises there; moreover, 20,000 people were trained, contributing to the creation of more than 10,000 jobs. Additionally, major achievements were unlocked in the EaP countries through the engagement of civil society representatives in governance and the public decision-making process, reflecting an intensified and more transparent dialogue with governmental institutions. On the other hand, good governance, EU’s top priority in the EaP region, is still a work in progress. Strengthening strategic communication by supporting plurality and independence of media, developing independent anti‑corruption bodies, public administration reforms, gender equality and non-discrimination issues, transparency in the economic and political areas – all still require attention.

In the field of economy, three Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTAs), which provide for mutual market openings on a stable and predictable basis, were established with some countries from the EaP region: Georgia and Moldova in July 2016, and Ukraine in September 2017. While focusing on the Single Market’s ‘four freedoms,’ that is free movement of people, goods, capital, and services, these improved the overall business climate, including curbing corruption, which in turn increased investor confidence. The key instrument in achieving these goals is the so-called legal adjustment: the partner countries have taken on extensive, binding commitments to align their laws and institutions with the EU acquis in order to stimulate political and economic development via institutional modernisation.

The DCFTA implementation process promotes the diversification of the EAP countries’ economies. For instance, Ukraine, whose economy is currently based on heavy industry and large firms, is trying to diversify towards the services sector and SMEs. Small and medium enterprises in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine can now access additional EUR 200 million in EU support grants, initiating new trade opportunities. Moreover, as part of the DCFTAs, the EU visa-free travelling possibilities have been opened in April 2014 for Moldova, in March 2017 for Georgia, and in June 2017 for Ukraine. With an aim to strengthen the business, social, and cultural ties with partner countries, the visa-free regimes is helping to promote human capital flows, deepen integration with the EU, and reinforce EU’s regional position as an important political and trading partner. EU exports and imports with Ukraine increased by 27.1%, and imports with Moldova by 7.7%, in the first year of the agreement’s adoption.

However, not all is a bed of roses. The legal basis for the DCFTAs, which are part of Moldova’s, Georgia’s, and Ukraine’s Association Agreements (AAs) and as such create a cooperation framework with EU, needs to be updated and streamlined, and the implementation of the Action Plans and the Roadmaps should be more precisely and realistically assessed, particularly when it comes to cost estimation. The multiplicity of plans, their overlap, and lack of synchronisation need to be eliminated. Given that most of the implementation is a complex, lengthy, and costly process, it requires elaborate and detailed planning. Sectorial strategies must be developed, and they need to inform the priority set in the National Action Plans.

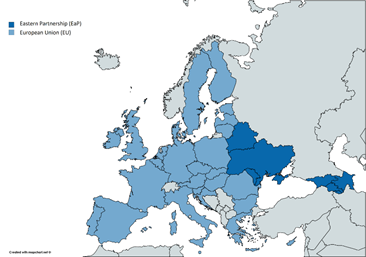

Source: own elaboration

The EaP works differently in each country, too. In case of Ukraine, the European Parliament passed ten resolutions related to the country, supporting development of democracy, implementing a far-reaching capacity-building inter‑parliamentary cooperation programme, actively observing elections, and promoting general political, economical, and social improvement. The EU also stands by Ukraine in other ways, including instituting and upholding sanctions against Russia, whose persistence marks the Minsk agreements’ incomplete implementation. This can only be seen as historically justified, given that Russia’s annexation of Crimea and aggression in eastern Ukraine started in the wake of the regime change in Ukraine, which itself followed from unrest over the then President Yanukovich’s decision not to sign the AA with EU in the first place.

Belarus participates in the EaP both bilaterally and in the multilateral formats. The EU support to Belarus is funded through the ENI for the period 2014-2020. Under the EU4Business initiative, 900 Belarussian enterprises have so far benefitted from loans, trainings and advice; 3,900 jobs were created. However, the EU’s relations with the country have been traditionally difficult and were developing much more slowly than those with the other EaP countries, reflecting many human rights and civil society violations. In 2015, Belarus showed a more open position for a dialogue with the EU and other EaP countries, becoming a hosting platform during the Ukrainian crisis. One of the reasons for that could be Belarus’s own fears of Russia in the face of the latter’s offensive actions in Ukraine. Since the Readmission Agreement was made in 2018, negotiations on visa facilitation and partnership priorities have been underway. Despite the extended cooperation under the EU‑Belarus Coordination Group in the last five years, the EU’s impact on enhancing governance and improving the human rights situation in the country is still disappointing. Many important challenges remain, especially in the area of human and employee rights, freedom of speech and media, and the capital punishment. In these respects, the EU continues the dialogue with Belarussian governmental bodies and the country’s civil society.

The EU-Azerbaijan relations, in turn, are based on a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) that entered into force in 1999, followed up by negotiations for a new comprehensive agreement that were launched in 2017, with the cooperation priorities endorsed in 2018. Azerbaijan plays an essential role in energy supplies to EU market, and through the EU4Business initiative, launched in 2016, the EU supports Azerbaijan in important infrastructure projects such as the Baku Port and the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway. Since the entry into force of the EU‑Azerbaijan visa facilitation and readmission agreements in 2014, the EU increased its support for the civil society development in the country. The main barrier for regional stability is still the Azeri-Armenian conflict in Nagorny Karabakh, the peaceful settlement of which is actively supported by the EU through its OSCE Minsk Group initiative and other peace‑building activities. Human rights, freedom of speech and of media, and gender equality remain equally important challenges in the EU-Azerbaijan relations.

The cooperation between the EU and Armenia intensified in 2013, when both parties were about to sign an AA, including a DCFTA. However, under a significant influence of Russian political pressure, Armenia eventually decided to join the Russia‑led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in 2015 and resign from signing the AA agreement. The EEU, established as a post‑Soviet reintegration effort – initially between Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus – is considered by the EU a geopolitical instrument to consolidate Russia's post-Soviet sphere of influence. The EU has declined to recognise the EEU as a legitimate partner until Russia meets its commitments under the Minsk agreements to end the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Continued EU-Armenia negotiations were finalised in a new Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA), signed in 2017. Armenia committed to take steps in economic modernisation and gradual adjustment to the EU acquis, as well as to substantially expand trade with the EU while respecting its obligations under the EEU. Unfortunately, gender violence continues to remain of serious concern in the country.

During the recent years, the division of the EaP countries into fast-track countries with strong European aspirations (Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine), slower‑track countries (Armenia and Azerbaijan) and very-slow‑track Belarus has deepened. The EU integration model has clashed with the EEU one, and the borderline countries were forced to make a choice between the two. Armenia, pressured by Kremlin, chose to join the customs union with Russia. Georgia and Moldova resisted and successfully signed DCFTA agreements with the EU instead during the November 2013 Vilnius summit. Ukraine, which hoped to follow similar path, was however faced with Russian aggression, a clear signal that, one way or another, defectors will be punished.

By: Vitaly Dorofeyev, CASE Analyst

Photo: European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker holds a news conference after the Eastern Partnership summit at the European Council headquarters in Brussels, Belgium November 24, 2017. REUTERS/Eric Vidal/ FORUM