showCASE 87 I Does it pay off to learn foreign languages? Evidence from Poland

Does it pay off to learn foreign languages? Evidence from Poland[1]

By: Jacek Liwiński, CASE Senior Economist

The progressing globalisation, accompanied by the growing international trade, foreign direct investments, and international labour migrations, cause the demand for foreign language competences grow, and according to forecasts this trend will continue in the future (Antonietti and Loi 2014; Isphording 2015). In the Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland, these changes intensified after the accession to the European Union. Suffice it to say that a significant increase in the inflow of foreign direct investments to Poland has been observed since 2004, and over 2.1 million Poles migrated to other EU Member States in the period 2004-2017. Under such circumstances, the command of foreign languages is becoming one of the key competences in the global labour market. Learning two foreign languages at school is obligatory in Poland, similarly to most European countries. Furthermore, there is a thriving sector of private language schools in Poland. In the European context, language skills are promoted by means of initiatives such as the Erasmus programme, which is co‑financed from public funds together with individual financial contributions. Since language education involves expenses, it seems interesting from the economic point of view whether this type of education brings any benefits to individuals in the labour market, and wage benefits in particular.

Why should foreign language skills increase wages?

The literature refers to three reasons why proficiency in foreign languages should influence earnings. First, foreign language skills can have a positive impact on productivity, since they enhance the effectiveness of communication at work. This includes both internal communication – with peers or managers – and external communication – with clients or suppliers (Ku and Zussman 2010). Secondly, learning a foreign language, and then using it, can translate into improved cognitive skills and, consequently, greater productivity at work. Adesope et al. (2010) shows that bilinguals have a cognitive advantage over monolinguals in the so called executive functions involving mental flexibility, inhibitory control, attention control, and task switching as well as creativity, flexibility, and originality in problem solving. Hence, the above two channels of the impact on wages correspond with the human capital theory, as they perceive the increments of skills to be the source of higher earnings. The third explanation refers to the signalling theory (Spence 1973). Based on it one can argue that the command of a foreign language may be a signal to employers of greater abilities and cognitive skills, thereby suggesting higher potential productivity.

What does international empirical literature show?

There are three strands of studies on the wage premium from foreign language skills. The first and the most popular one covers the wage premium earned by immigrants in the host country. It is well established in this literature that immigrants with the host country language skills obtain a positive wage premium. The second group of studies refers to the wage premium from bilingualism obtained by natives in multilingual labour markets. Most of those studies show that proficiency in a second language is remunerated in the labour market. The third and final strand of literature focuses on the wage premium from the command of foreign languages earned by the natives. Most of these studies concentrate on the command of English, with only a few analysing premiums from other languages (see: Ginsburgh and Prieto-Rodriguez 2011; Williams 2011; Di Paolo and Tansel 2015). The literature in this stand finds a positive wage premium from the command of English, while in some countries – from other foreign languages, too.

What does our analysis show in case of Poland?

Our analysis is based on the Human Capital Survey (BKL) for the period of 2012-2014.[2] The survey is a unique source of data on human capital resources of Poles, and it also provides information about the situation of individuals in the labour market. Importantly for this study, the survey questionnaire contains questions about foreign language skills. Respondents were asked to list all languages they were familiar with and to assess the level of command for the three languages they knew best (using a six‑grade scale) in four linguistic competences: reading, writing, speaking, and listening comprehension. Our sample consists of 14,145 individuals who were self-employed or employed on a contract and who reported their earnings.

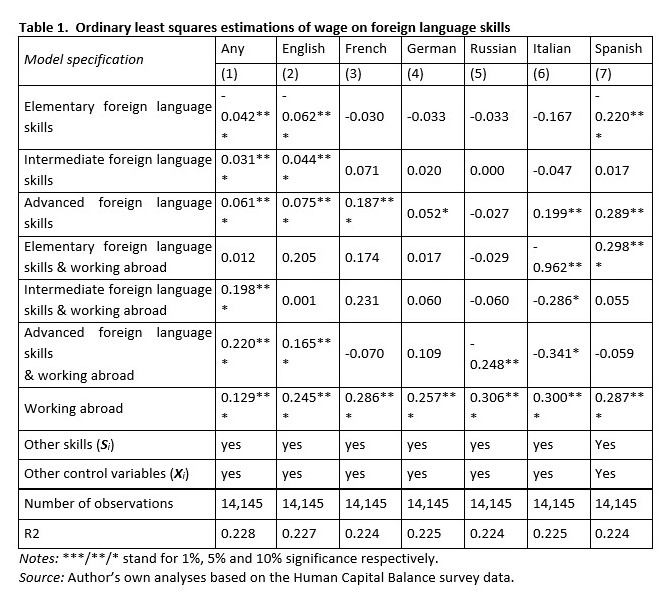

We estimated hourly net earnings[3] through regression analysis (ordinary least squares), with our independent variables being the level of foreign language skills (basic, intermediate, and advanced) and the circumstance of working at home or abroad, while controlling for respondents’ other skills (Si) and other factors that may have an impact on earnings (Xi). The results of estimation, presented in Table 1, show that an advanced command of a foreign language yields on average a wage premium of 6% to individuals working in Poland and as much as 22% to those working abroad.

What is interesting, the respondents employed in Poland obtain a wage premium from an advanced command of almost any of the languages covered by the analysis. The premium is particularly high from advanced knowledge of Spanish (29%), Italian (20%), and French (19%). The premium from an advanced command of English and German is much lower (8% and 5%, respectively). Such a substantial difference may be due to the fact that the command of the first three languages referred to above is very rare among Poles (these languages are declared by 0.4%, 0.8% and 1.7% of the respondents, respectively), while the last two are much more common (34% and 16% respectively). Interestingly, the command of Russian does not bring any wage benefits at all. This outcome may be depressing especially to individuals who studied in Poland before the economic transition, as learning Russian had been mandatory in Polish schools and universities until 1990.

Another interesting finding is that English is the only foreign language the command of which has a positive impact on wages earned abroad. Individuals with an advanced command of this language earn 16.5% more when working abroad and 7.5% more when working in Poland. Furthermore, English is the only foreign language bringing a wage premium while working in Poland, even if the command is intermediate (4.4%).

Conclusions

The analysis presented above shows that, in general, foreign language skills yield wage benefits to Poles. Yet, these benefits are strongly differentiated, depending on the language and on whether one is employed in Poland or abroad. It seems that it is definitely worth to learning Spanish, Italian, and French, as fluency in these languages yields very high wage premiums (29%, 20%, and 19%, respectively). The wage returns to fluency in English or German are lower but positive (8% and 5%, respectively). On the other hand, fluency in Russian is not rewarded at all on the Polish labour market. As far as employment abroad is concerned, only proficiency in English brings wage benefits (16%).

Finally, the results of the analysis justify public and private investments in the development of language competences. The progressing globalisation and the resultant growth of demand for language competences suggest that investments in learning foreign languages will translate into wage benefits in the future, too. In this context, the special role of English is worth stressing. It is the only one of the languages covered by the analysis that, if adequately mastered, brings wage benefits both in Poland and abroad. Therefore, proficiency in English seems to be one of the key competences on the contemporary labour market.

[1] This text is a part of the working paper: Liwiński, Jacek, 2018.‚ ‘The Wage Premium from Foreign Language Skills,’ GLO Discussion Paper Series 251, Global Labor Organization (GLO).

[2] The Human Capital Survey was conducted in the years 2010-2014 by the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development (PARP) in co-operation with the Jagiellonian University.

[3] The earnings are expressed in 2014 prices.